Lassen Volcanic

Lassen Volcanic

By Tim I. Purdy

Softcover, 6×9, 206 pages,

ISBN: 978-0-938373-93-5

Price $19.95

[Out of print]

Light My Fire was 1931 Park Superintendent Lynne Collins theme who staged a fake eruption on top of Lassen Peak, not to be confused with the The Doors, 1966 hit song. The latter met with rave reviews, Collins experiment did not. In many ways it set the stage for one of the nation’s oldest national parks, approaching its centennial in 2016. While Lassen is not a headliner compared to other parks, it does have a colorful past. First there was a lot of political bickering from inception to the problematic purchasing the inholdings scattered throughout the park—Drakesbad, Manzanita Lake, Supan Sulpur Works, Juniper Lake to name a few.

Lassen Volcanic brings a fresh perspective to its history, revealing new information gleaned not only from the Park’s archives, but the Sifford papers too. It is a great way to get reacquainted with the park and explore it again.

Lassen Volcanic National Park – A History

The history of Lassen Volcanic National Park is an intriguing one, and with thought in mind, work on a comprehensive history is now being undertaken. Fortunately, several people such as Eunice Colburn, Paul Schulz, Douglas H. Strong and Roy D. Sifford, have been instrumental chronicling the Park’s past.

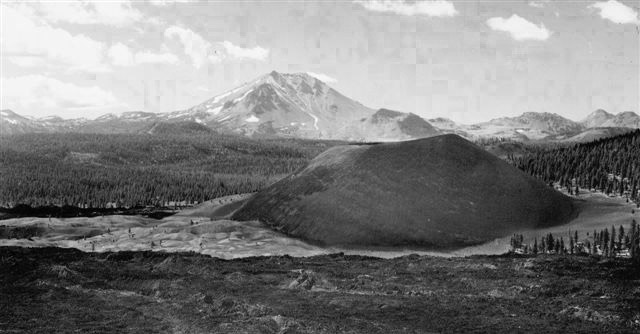

Mount Lassen , Cinder Cone, and the Parks various hydrothermal features and lakes have captured the attention of many over the years. While on a prospecting trip in the summer of 1851, Grover K. Godfrey, along with a prospecting party of nine other men, made the first known ascent to the mountain’s summit. Godfrey observed from this vantage point at the top, “The sight is unrivaled in beauty and magnificence. Its like the vision of some dream land. I fancied I could see all the kingdom of this world at one glance.”

In the fall of 1863, as a part of the geological reconnaissance survey of Northern California, Josiah D. Whitney of the California State Geological Survey sent four men to conduct field work—William H. Brewer, Clarence King, James T. Gardiner and Richard Cotter. In September 1863, they climbed Mount Lassen to examine the lava flows among other things. Brewer, like Godfrey, was also in awe of the view. Years later Brewer exclaimed, “Although I have often reached greater altitudes, that day stands out in my memory as one of the most impressive in my life.”

This party was one of many scientific studies conducted in the late 1800s of the Lassen region. In August 1872, John Gill Lemmon, noted botanist, surveyed the plant life around Mount Lassen . Next to make an appearance was Harvey W. Harkness, in 1874, to determine the last eruption of Cinder Cone that he estimated as recently as 1851. In the scientific circles it was Joseph Silas Diller who would spend nearly forty years, on an irregular basis, studying the mountain until his death in 1928.

Yet, it was the summer tourists who were truly having a field day exploring Mount Lassen . One of the earliest pleasure seekers to climb the mountain also left a lasting legacy. On August 28, 1864 , Aurelius and Helen Brodt, Pierson B. Reading and others made the ascent to the top while camping at nearby Morgan Meadows. Helen became the first woman to climb Lassen. They came across a small lake high on the mountain, and Reading immediately proclaimed it “ Lake Helen .”

It was the summer resorts of Dr. Willard Pratt and L.W. Bunnell at Big Meadows (now Lake Almanor ) that extolled the splendor of Mount Lassen from their establishments, especially since there were so few resorts near the mountain. They advertised the Mount Lassen experience as a wonderful day outing from Big Meadows. In addition, Mount Lassen was not the only star attraction. Cinder Cone and the many lakes also garnered attention. One of the biggest draws was that of the hydrothermal activity. Visitors examined these natural curiosities with such intriguing names as Lake Tartarus ( Boiling Springs Lake ), Devil’s Kitchen and Bumpass Hell. By 1878, Thomas Malgin had built a crude bath house in Warner Valley for those who wished to indulge in a soak of the hot mineral waters. As one Big Meadows’ correspondent wrote in 1872, “The hot springs and Boiling Lake are attracting much notice this summer. Three parties amounting to thirty-two visited the springs last week and another party of fourteen start tomorrow.”

In 1890, three national parks were established in California —General Grant, Sequoia and Yosemite . At that time it was suggested that Mount Lassen and its unique volcanic features warranted national park status. In 1902, when Crater Lake was made a national park, again it was discussed that Lassen also qualified for such distinction.

In the spring of 1906, petitions were circulated in Lassen and Plumas Counties asking President Theodore Roosevelt to make Lassen a national park. The appeal went unanswered. Hope was on the horizon with the creation of the national forests. Forest Supervisor Louis Barrett was assigned a multitude of tasks on the Lassen National Forest . One of his major accomplishments was the submission to make Mount Lassen and Cinder Cone National Monuments . On May 6, 19 07 , President Roosevelt signed into law, making Lassen Peak (1,280 acres) and Cinder Cone (5,120 acres) as National Monuments.

On November 8, 19 10, John E. Raker was elected to Congress from California’s First District, by a narrow margin of 124 votes. Raker campaigned on a conservative platform, and embraced Gifford Pinchot’s forestry policies. In his first year in office, Raker introduced bills to create Redwoods National Park and Lava Beds National Monument, though neither passed.

In 1912, Raker introduced a bill to create Peter Lassen National  Park . Raker was no doubt influenced by his wife Iva Spencer’s family. The Spencers would horseback ride from Susanville to Drakesbad during the summers—it being one of their favorite places. His mother-in-law, Lucy Philenda Spencer is credited in suggesting that the Lassen region be made a national park. Raker’s bill received favorable review from the Department of the Interior, yet it failed to make it out of committee. In 1913, Raker again introduced the bill to create Lassen as a National Park, as well as one to create a Mount Shasta National Park . Raker had met with some opposition to the Lassen Park proposal, but that was all about to change.

Park . Raker was no doubt influenced by his wife Iva Spencer’s family. The Spencers would horseback ride from Susanville to Drakesbad during the summers—it being one of their favorite places. His mother-in-law, Lucy Philenda Spencer is credited in suggesting that the Lassen region be made a national park. Raker’s bill received favorable review from the Department of the Interior, yet it failed to make it out of committee. In 1913, Raker again introduced the bill to create Lassen as a National Park, as well as one to create a Mount Shasta National Park . Raker had met with some opposition to the Lassen Park proposal, but that was all about to change.

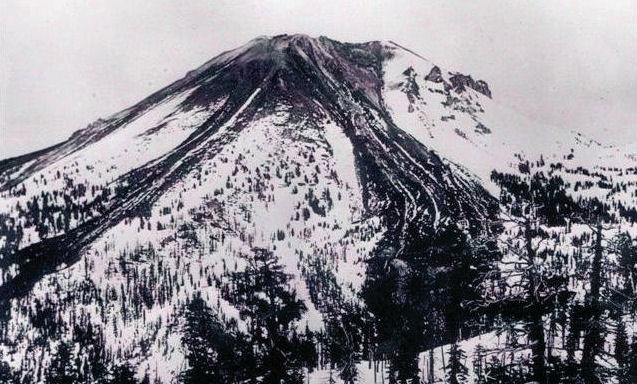

During the late 1890s and early 1900s residents were reporting rumblings and other disturbances around Lassen. Of course everyone had an opinion as to what they were or were not. That all changed on the morning of May 30, 19 14, when smoke was spotted emitting from the mountain top. At first it was dismissed and a forest service crew climbed the peak to discover, that yes not only were steam and ashes spewing forth, but there was a new crater. The mountain continued with its rumblings, and on June 14, 19 14, a violent eruption occurred leaving no doubt in anyone’s mind that the continental United States had its first active volcano. The eruptions continued throughout 1914 and into the early 1920s. Yet, it was on May 22, 19 15, that witnessed the “great eruption” wherein among other things sent forth a mushroom shaped cloud four miles into the atmosphere.

There was a lot of speculation as to what was caused the initial eruptions. Many of the old time Big Meadow residents attributed to the eruptions to the filling up Big Meadows with water to create Lake Almanor!

Mount Lassen’s eruptions facilitated its inclusion as a National Park. On August 9, 1916, the Lassen Volcanic National Park was created, with President Woodrow Wilson’s signature. August 1916 was certainly a hallmark month, with not only the creation of Lassen, but on August 1st the Hawaii National Park was signed into law and equally important on August 25th, the National Park Service was created to administer the thirteen national parks that had been established since 1872.

One of the main obstacles to the development of Lassen Park was that Congress did not appropriate any funding for such. Thus, a compelling story unravels with the formation of the Lassen Volcanic National Park Association. One way they raised awareness of the public in the 1920s was their “socialability runs.” Groups from as far away as Sacramento drove to tour the park, and in one instance attempted to travel over the Nobles Emigrant Trail. Another issue concerned the private property inside the park boundaries such as the key attractions of Supans and Drakesbad, which by coincidence were the most accessible. The latter took decades for the park to acquire.

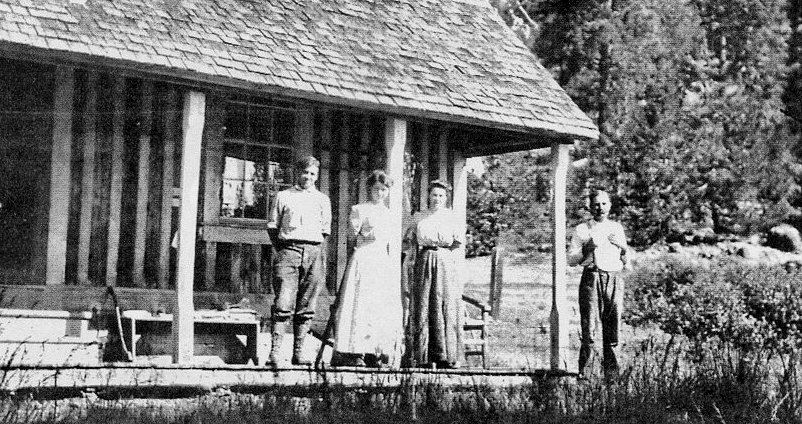

Drakesbad

One of the intriguing characters of the Mount Lassen region was that of Edward Russell Drake (1830-1904). A native of Maine , Drake arrived in the California gold fields in 1851, and by 1859 he had settled in Plumas County . During his early tenure, Drake explored much of northern Plumas County . In 1863, Drake was hired as a guide to lead an expedition for the California Geological Survey so they could conduct a reconnaissance survey of Mount Lassen . In 1884, Drake suffered some medical problems and spent an extended stay at the Gilroy Hot Springs. The following year Drake sold his saloon at Butt Valley , Plumas County and relocated to Warner Valley to what eventually became Drakesbad. In the summer of 1900, Susanville resident, Alex Sifford arrived at Drake’s for health reasons. The experience was so beneficial that Sifford bought the place that fall from Drake for $6,000, beginning the saga of Siffords at Drakesbad.

More can be learned by this link http://drakesbad.com/index.php/drakesbad-history

Your Lassen Experience

If you happen to possess any historical documentation and/or stories about the Park whether it be climbing Mt. Lassen , fishing at Butte Lake, hiking around Bumpass Hell or as guests at Drakesbad or Manzanita Lak , or in the happenstance you or a family member were a former Park employee, I would truly enjoying hearing from you.